Last week we introduced you to the basics of behavioral economics. This week we look at how we can apply those insights towards social change efforts using two frameworks: behavioral mapping and MINDSPACE.

Remember, there are no silver bullets here. Multiple tools and approaches are required in order to understand the current situation AND be able to design effective interventions that inspire and sustain new behaviors.

Tackling the "last mile"

Behavioral economics plays a vital role in diagnosing what's driving current behaviors and increasing our effectiveness in designing interventions to shift those behaviors. While behavioral insights alone aren't sufficient to solve most of the complex social issues we face, ignoring them is a sure way to limit our effectiveness.

When we ignore behavioral insights, we run into the "last mile" problem as described by Sendhil Mullainathan in his TED Talk Solving Social Problems with a Nudge:

See, we spent a lot of energy, in many domains -- technological, scientific, hard work, creativity, human ingenuity -- to crack important social problems with technology solutions. That's been the discoveries of the last 2,000 years, that's mankind moving forward. But in this case we cracked it, but a big part of the problem still remains. Nine hundred and ninety-nine miles went well, the last mile's proving incredibly stubborn.

While we've created technical solutions to many of the issues facing our society (diarrhea, malaria, diabetes, agriculture, energy efficiency), these solutions aren't effectively reaching those who are most in need. The last mile feels painfully long.

Luckily, there's a number of experts hard at work applying behavioral insights to complex social challenges. We begin by exploring behavior mapping, a framework for diagnosing the root of why certain behaviors fail.

Behavior mapping

Many times you'll analyze a given issue and find that the behavior of certain stakeholders just doesn't make sense. If you've arrived at this point, it should be a warning sign that more work is required to get the full picture.

Maybe you don't fully understand their context and there are entirely rational reasons for their behavior. Maybe one of the many [cognitive biases][2] is influencing them to act irrationally. Maybe they have a worldview that doesn't align with yours.

Whatever the source of the disconnect, consider using behavior mapping to get at the root of the problem. Behavior mapping is a technique that analyzes a behavior by breaking it apart into three stages: intention, action and follow through ([Datta & Mullainathan 2012][1]).

Stage 1: Intention

Did they really intend to take the action? Did they say they would but had no real intention of following through?

If they never intended to take action, you need to get to the root of why. Maybe they have a mental model which is at odds with the desired behavior. Consider the problem of diarrhea in developing countries referenced by Datta and Mullainathan:

A child with diarrhea is constantly leaking fluids. Given this, a perfectly plausible mental model of the disease would imply that putting any more liquids into the child will only make it sicker; keeping the child “dry” is better.

Indeed, when poor women in India are asked whether the solution to a child with diarrhea is to increase or decrease its fluid intake, 35%-50% say that the answer is to decrease it.

In this case, working to shift the mental model should be your primary goal. Are there respected members of the community that have used rehydration techniques successfully who can share their experiences and teach others? Is there a way to design a rehydration solution that uses solids rather than liquids?

Stage 2: Action

If the intent is there, did they actually take action? Did they intend to take action but never got around to it? Did they change their mind and decide it wasn't the right action to take?

Many times we (and our environments) are our own worst enemies. We know what we should do, but keep putting it off until tomorrow. Low and behold, tomorrow never comes.

If you discover it's a problem of getting over these hurdles, it's a much different approach than if the intention isn't there. You might make the desired behavior the default choice so there's no hurdle. You might offer a small, immediate incentive to overcome the hurdle. You might get them to make a public commitment to take action. Or you may find ways to demonstrate that the desired behavior is the norm.

If intention is there but action is lacking, look at their social network. Is there social pressure against the desired behavior? Is the dominant norm fighting your efforts? Is there competitive messaging pushing for a different behavior?

Stage 3: Follow through

Did they initially adopt the right behavior but fall off? Is the behavior sporadic at best and thus lacking impact?

We all have limits to our self control. Unfortunately, the way some policies and programs are designed only makes this worse.

Sometimes we can change the structure of programs. Rather than disbursing funds in lump sums that require the discipline to save over an entire year, change payments to be monthly or weekly. Remove the burden of following through by making things automatic, or as easy as possible (a great example of this is fortifying current food choices rather than expecting people to shift their eating habits).

Sometimes we can help strengthen people's ability to follow through. Create a commitment device by having people state their intentions publicly, build in incentives for following through, or find creative ways to allow self-inflicted punishments for not following through.

To recap, behavior mapping provides a valuable framework for identifying why desired behaviors aren't being adopted and creating solutions to overcome any hurdles in the way.

Next we look at the MINDSPACE framework to guide your policy and strategy design.

MINDSPACE: Influencing behaviour through public policy

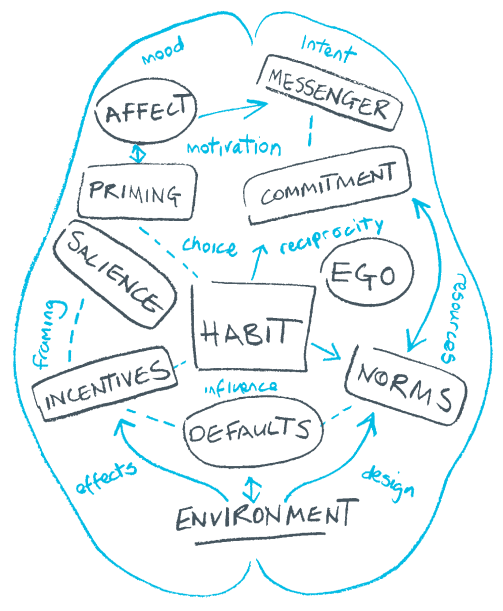

MINDSPACE is a framework published by The Institute for Government that outlines nine key influences on behavior that should be considered when shaping policy. We find these categories helpful as a checklist when preparing to implement any strategy that involves behavior change.

The MINDSPACE Framework by the Institute for Government.

- Messenger. Who delivers the message matters. Have we been deliberate in our choice of messenger and is it the right choice for all audiences? Are we using experts to deliver messages and looking for messengers with demographic and behavioral similarities?

- Incentives. Our response to incentives are shaped by mental shortcuts. Are we choosing smaller, immediate incentives? Are we framing our language in terms of what someone stands to lose?

- Norms. We tend to follow the crowd. Can we frame the desired behavior as the norm by telling people what others do in the situation? Can we make the desired behavior more visible in the respective social network?

- Defaults. We tend to go with the default. Are we consciously choosing a default that would be in the best interest of most people?

- Salience. We have limited attention which is drawn to what seems novel and relevant. Are we using novel, accessible, and simple messages? Are we relating to people's personal experiences?

- Priming. We are often influenced by subconscious cues. Are we paying attention to these cues and removing those that are potentially damaging? Are we being ethical in our use of primes?

- Affect. Our emotions shape our actions. Are we eliminating emotional triggers and helping ensure people make decisions in an ideal emotional state?

- Commitments. We want to stick to our promises and reciprocate acts. Are we helping people stick to their decision using public commitments? Are we making the most of people's tendency to reciprocate?

- Ego. We act in ways that make us feel better about ourselves. Are we finding ways to increase self-esteem in our intervention? Are we building on people's desire to appear consistent? And are we aware of people's tendency to overrate their abilities and taking steps to mitigate any negative effects?

If you're interested in diving deeper, we recommend reading the full MINDSPACE report.

One of the big takeaways from behavioral economics is that details matter. You can spend immense time and energy shaping policy and designing new technologies only to fail in the implementation because you ignored the details. Donald Marron describes this well in relation to Obama's new nudge brigade:

These examples run the gamut from the life-changing to the almost trivial. But they illustrate a common theme: details matter. Policy debates usually focus on high-level issues. Should health insurance be offered on exchanges? Should student loan repayments be limited as a share of a borrower’s income?

But after such issues are settled, their impact depends on how policies are implemented. The nitty-gritty of designing forms, deciding how and when to prompt people, and framing and communicating options really matter.

Examples

Now that you're armed with frameworks on how to apply these insights, spend some time exploring how behavioral insights have already been applied in complex social issues. Below are a few of our favorites:

- Poverty Interrupted

- Thinking, Fast and Slow? Some Field Experiments to Reduce Crime and Dropout in Chicago

- Reframing HIV Risks

A closing thought from Sendhil Mullainathan

You see, we tend to think the problem is solved when we solve the technology problem. But the human innovation, the human problem still remains, and that's a great frontier that we have left. This isn't about the biology of people; this is now about the brains, the psychology of people, and innovation needs to continue all the way through the last mile.

Check out Sendhil's full TED Talk below:

[1]: http://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/Datta_Mullainathan_Behavioral_Design.pdf [2]: http://blog.kumu.io/introduction-to-behavioral-economics/