These days everyone is familiar with some type of network – whether that's their professional network on LinkedIn, their social network on Facebook, or the informal web of relationships within your local community.

But there's a distinct difference between a network as a structure of relationships and a network as a tool for driving change. The latter is what we'll focus on today (and how visualization can help you along that journey).

The term we use to describe networks of this type is intentional networks. June Holley, author of The Network Weavers Handbook and long-time practitioner of all things networks, describes an intentional network as:

...a network of people and organizations that are working on the same issue or vision, together with structures that have been created to mobilize the energy of the organizations.

Intentional networks have shared purpose. They use network principles to design how they make decisions and coordinate projects. And they show up in the world in different ways than traditional, top-down authority structures.

Whether you're thinking of launching a new network or you're neck-deep tending to an existing one, here are a few tips to guide the development of your intentional network:

- Align around shared purpose and values

- Know the stage of your network

- Act intentionally to strengthen your network

- Hold each other accountable to working like a network

- Wait to add structure until you need it

- Don't underestimate the challenge

This week we're covering the first three tips. Check back next week for the final three!

Align around shared purpose and values

Shared purpose and trust-based relationships are the glue that hold intentional networks together – they keep people working together even when significant conflict emerges.

It's important to be realistic and understand that shared purpose doesn't happen in a one-day retreat, let alone the 1-hour sessions many people dedicate to this work. It takes time, ongoing conversation, and space outside of formal gatherings to ensure people are getting to know each other on a personal level.

So where do you start? Rob Ricigliano, Systems and Complexity Coach for The Omidyar Group and long-time negotiation and mediation expert, introduced us to the "guiding star / near star" technique to help get the conversation started and make sure everyone's on the same page.

- guiding star: The guiding star should be framed as the shared desired future your initiative is working toward. It is not time bound and will serve as a navigational tool as your initiative moves forward and adapts over time.

- near star: The near star should be framed as a distant but foreseeable outcome that could be attained in the next few years. It should be a significant step toward your guiding star.

Here's an example from the Hawaii Quality of Life project:

- guiding star: Hawaii produces a quality of life that is sufficient and sustainable for all its residents

- near star: Oahu eliminates chronic homelessness

As you're flushing out the shared purpose, beware of the difference between what David Peter Stroh refers to as the "espoused purpose" and the "operative purpose". For example, while the director of a homeless shelter may wholeheartedly agree with an overall purpose of ending homelessness, her day-to-day reality may not be aligned with that vision. The more beds the shelter fills, the more money the shelter gets. Ignore these competing priorities at your own peril.

Know the stage of your network

A healthy network is a resilient network. That means having any one person play too central of a role is dangerous. What happens if that person leaves? What happens if they become a bottleneck?

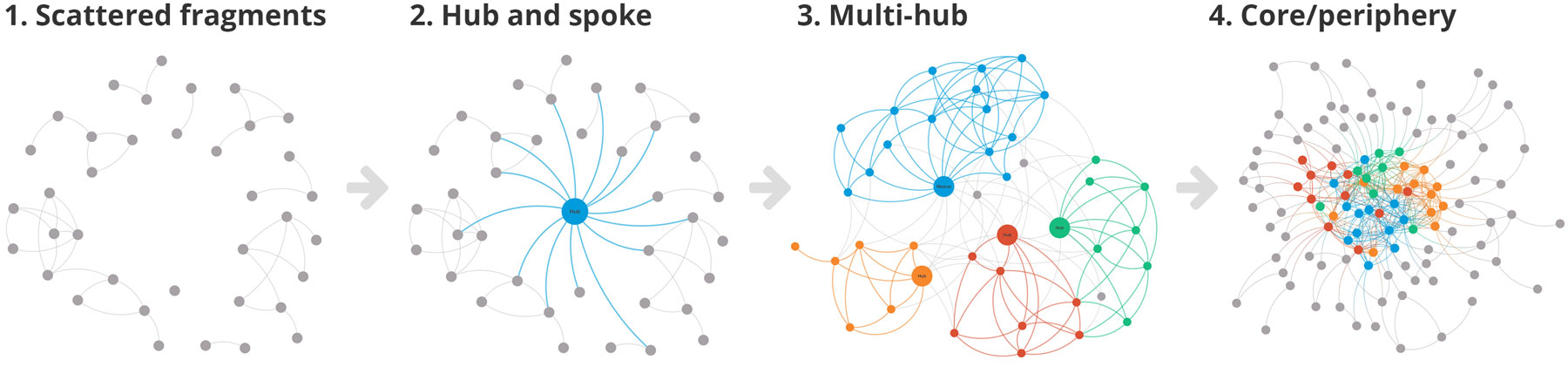

It's tempting to think that networks burst forth onto the scene fully formed, but in reality building a network takes time and evolves through many stages. We were first introduced to the four stages of network development by June Holley and have found it immensely valuable in thinking about the health of a network:

The stages focus primarily on the structure of the network. While structure isn't the only measure of a network's health, it's a great place to start. You can think of each stage as follows:

- stage 1, scattered fragments: When a network is just coming together (or before it even forms and you're simply identifying people who may be potential members), you're often in the scattered fragments stage. Certain people know each other, but there are lots of silos and not much interconnection.

- stage 2, hub and spoke: The birth of a network usually requires the effort of some central hub. This is one of the fascinating contradictions of growing a healthy network. A healthy network would very much discourage someone playing such an overly central role, but when you're in the early stages of building a network, it is essential that someone play this role, connecting across the various fragments. The key is to serve in this role and then move out of the center as quickly as possible.

- stage 3, multi-hub: As the network continues to develop, you're identifying multiple people who can play the role of hub, creating more and more trust-based relationships across the network. Some of these hubs might have formal coordinating roles (network weavers and project managers), while others may be more informal (the natural connectors in your network).

- stage 4, core/periphery: At this stage you have a dense, interconnected core with multiple hubs overlapping in that core. No one person is playing the central role. In addition to that, you've cultivated a periphery that is large (ideally 5x the size of the core) and diverse. This is what June refers to as a "smart" network. The large and diverse periphery serves as a source of new ideas and innovation for the network.

It can be difficult to know which stage you're at unless you take the time to visualize your network. This is often done by surveying the members of your network, asking a series of questions to discover who is connected to who as well as what projects they are interested in working on. By taking snapshots of your network over time, you can see how your network is growing (and more easily make the case for why continuing to invest in supporting the network is worthwhile).

The simple act of seeing the map of their fragmented network moved the groups to action.

Barr Foundation, Working Wikily

See Building Adaptive Communities through Network Weaving by Valdis Krebs for more information about the phases of network development.

Act intentionally to strengthen your network

Once you know what stage your network is in, how do you move from one stage to the next? Do you just plan lots of meetings with good food and free drinks, then wait and see what happens? While that unfortunately seems to be a common strategy, you'll have more success adopting the mindset of network weaver.

Network weaving is a term introduced by June Holley and it's a beautiful metaphor for the deliberate and skilled act of building a network over time, starting with simple ingredients (people, relationships, trust, shared values) and building a rich tapestry that is the intentional network. We can think of this work in four major buckets:

- Connecting people and building strong relationships

- Helping people initiate and act with others (self-organizing)

- Understanding the system you are trying to change

- Supporting the network

Each of those buckets deserves a blog post of its own (heck maybe even a book!). If you're interested in diving deeper, I highly recommend buying June's Network Weavers Handbook. In the meantime, here are a few things you can start doing today to build a stronger network:

- Close triangles. Are you connected to two people who aren't connected to each other? Make an introduction! Encourage everyone in the network to do this and you'll be surprised with the result. Remember to focus on quality over quantity.

- Spark micro-collaborations. June calls these twosies and threesies and they are small projects that build everyone's collaborative muscles. Encourage people to start these on their own – self-organizing is a core principle of a healthy network. It's even better if you have an innovation fund to support some of the minor costs that inevitably come up with these smaller projects.

- Cultivate a large and diverse periphery. Always be on the lookout for ways to invite new people to participate in the network and make room for many different levels of involvement. Not everyone can or wants to be involved in weekly/monthly meetings, but that doesn't mean they should be excluded from the network.

- Share learnings and identify high-leverage projects. Micro-collaborations are more than opportunities to practice collaboration. They are also experiments about what works and doesn't work in changing your system. Make sure you have a process for sharing learnings across your network and using those learnings to identify the larger, high-leverage projects that have the potential to really make a difference.

That's all for now. Go forth and weave boldly! And don't forget to check back next week for part 2!