People use Kumu across lots of sectors and disciplines to improve the way they visualize and communicate complex relationships. Today is the first of a new series we’re launching titled How do you Kumu? that explores the processes and approaches of our most active users.

We’re starting the series by diving into a practical guide to systems mapping with Rob Ricigliano, a skilled systems thinker who’s worked with organizations such as:

- USAID

- The Department of Defense

- Humanity United

- Omidyar Network

- and many more

Rob is also the author of Making Peace Last, a toolbox for sustainable peacebuilding, and co-founded the Master of Sustainable Peacebuilding program at the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. He also served as Associate Director of the Harvard Negotiation Project.

We sat down with Rob to get an “under the hood” look at how he approaches this work.

Framing the work

There isn’t a “one size fits all” approach to systems mapping. You’re normally choosing between one of three general approaches to this work:

Systems mapping as a mostly internal process

You’re helping a team or an organization clarify it’s own thinking and ensure that it is dynamic and systemic (not linear and overly focused). This includes both its theory of the context (the dynamic environment within which they are working) as well as its theory of engagement (how they can best work with that complex system to make positive change over time in ways that affects core system dynamics).

Systems mapping as an intervention in itself

You’re bringing together key stakeholders, actors and partners to build a map in a participatory way and thereby affect the thinking and behavior of these key folks. This is the messiest of approaches, purposely colliding opposing viewpoints, holding the tension, and moving the group towards shared understanding of the system.

Systems mapping as a hybrid

You’re looking to enrich and validate your internal thinking against the perspectives of external resources/experts. It isn’t fully participatory, but expands beyond the team/organization in terms of who is involved.

It’s important to take the time to clarify your approach up front. If you’re using a participatory approach, building a diverse and influential group of stakeholders to participate in the process is a key first step. If you’re using it as an internal process, developing the buy-in of key managers and influencers within your organization is important. One approach isn’t better than another - there are benefits as well as transaction costs to each approach. Take the time to think deeply about which approach is right for your particular circumstance, and don’t take the easy way out.

Building the map

Once you’re set with an approach, where do you start? If you’re looking to create an open space that accommodates a wide variety of perspectives (especially important in participatory approaches), a good process to start with is an enabler/inhibitor analysis (described below). You may use an abbreviated version of this process when you have less need for broad buy-in, are further along in the research process and have already canvassed lots of views, or are facing other time pressures, but it almost always creates a lot of value.

Start by identifying enablers and inhibitors, then group into common themes

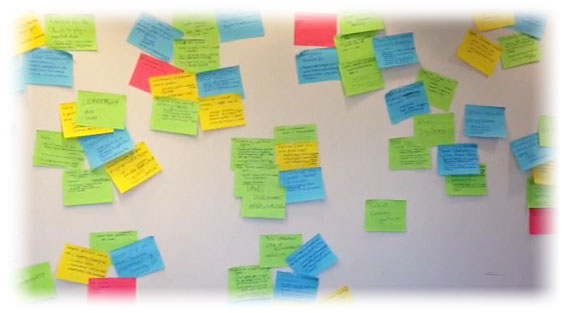

Start by asking individuals to identify what factors they see as being key “enablers” of the issue they care about (e.g. healthy elections, quality of life, effective reform) and what they see as key “inhibitors” or things that negatively affect the issue they care about (e.g. what weakens the legitimacy or effectiveness of elections, reduces quality of life, or frustrates attempts at reform). We'll usually ask people to write these factors on post-its and then put them up on a wall or whiteboard. In order to bring some order to all of the individual ideas people generate, ask them to start grouping enablers and inhibitors into themes (e.g. enablers that relate to the link between housing and quality of life).

Once people start to identify these themes, a great way to get them to deepen their understanding of those factors and start identifying causal relationships with other factors is to have them look both upstream and downstream from the factors they've already identified. What influences this factor? What does this factor influence?

After the groups have spent time brainstorming possible upstream and downstream factors (and their interconnections), we often reconvene so that different groups can see and comment on the thinking of other groups. This is a great opportunity for the individual groups to share across teams, and helps bring to life what factors present themselves most frequently, and also which factors were a surprise.

Include structural, attitudinal, and transactional factors

Often, when we ask groups to do their upstream/downstream analysis of key factors, we ask them to think in terms of structural, attitudinal, and transactional causes (upstream) and consequences (downstream) of the key factor they are working with. Here's how to think of each:

- Structural: The systems (e.g. rule of law, economy) and institutions designed to meet people’s basic human needs

- Attitudinal: The attitudes, norms, and intergroup relationships that affect the level of cooperation between groups/people

- Transactional: Processes and skills used by key people to manage conflict, solve problems, and turn ideas into action

It's important to make sure you're thinking of factors in each category in order to build an understanding that is holistic (looks at very different aspects of a system) and spans varying time scales (e.g. the impact of some causes or consequences are quite immediate while others take longer to occur).

Think of it this way: transactional changes operate on the fastest time scale and often spur both structural and attitudinal changes. Structural changes are slower, often requiring legislation, funding, and expensive implementations. Attitudinal changes are by far the slowest, many times taking decades to shift. It's far easier to train someone how to negotiate (transactional) than it is to change long held cultural beliefs towards certain groups of people (attitudinal).

Use those factors to create feedback loops of the core patterns and dynamics

You now have a probably somewhat overwhelming list of factors. While having a comprehensive list is important, it's easy to get too far into the weeds if you just continue down the path of identifying more and more factors. Remember, don't lose the forest for the trees!

At this point we ask people to take the factors they've identified (and the many connections they’ve identified between those factors) and start connecting them into feedback loops that represent the core patterns and dynamics of the system. At this point we have to introduce two concepts: 1) same vs. opposite connections, and 2) balancing vs. reinforcing loops:

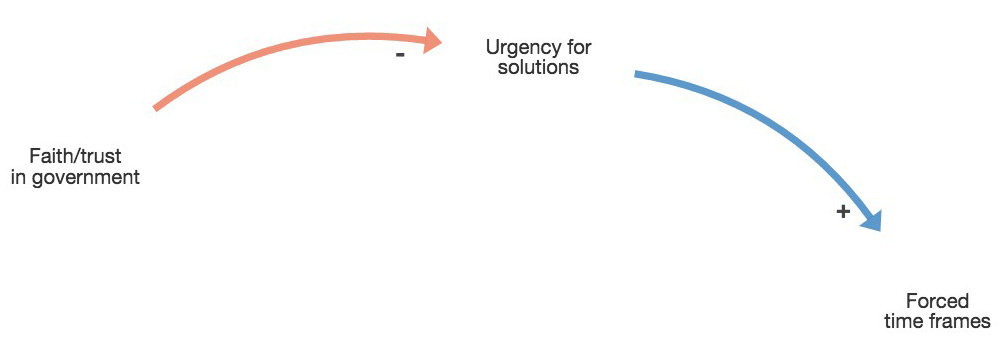

Same vs. opposite connections

As people work towards building their first loops, they first have to start connecting individual factors to one another. As they do this, it's important to ask what effect a change in one factor has on the other. If factor A increases, will factor B also increase? If the answer is yes, it's a "same" connection. If the answer is no, it's an "opposite" connection.

Same and opposite connections can be represented by writing "same (s)" or "opposite (o)" on the connection itself, or you can put a plus or minus sign on each end of the connection to note the nature of the relationship. For example, "+/+" or “-/-“ is used for relationships that are the same (e.g. +/+ means the more of one factor leads to the more of another) and a "-/+" or “+/-“ for opposite relationships.

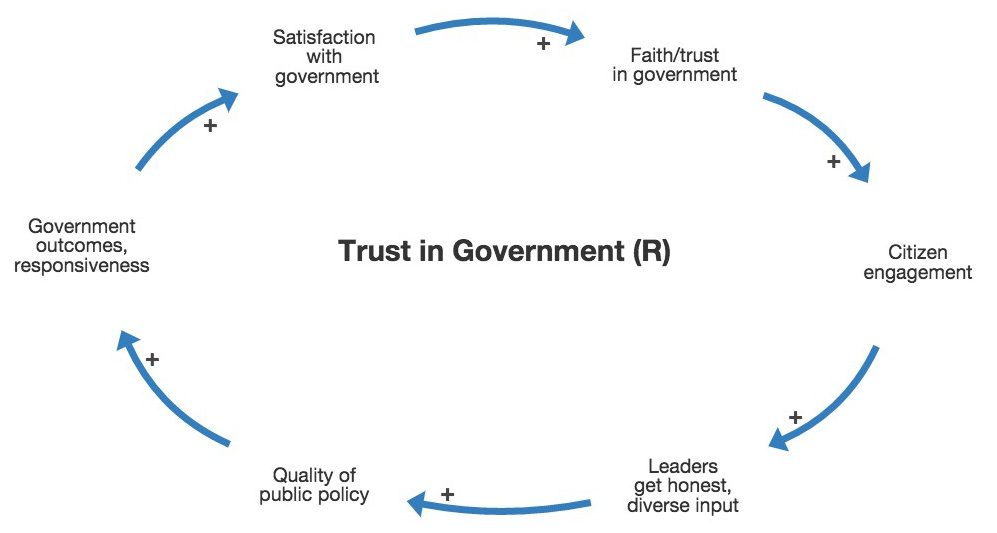

Balancing vs. reinforcing loops

Once you've created a loop (you'll know you have one when you're back to where you started by following the connections on the map), you'll want to categorize the loop as either balancing or reinforcing. You can do this by counting the number of opposite connections in a given loop. If the number of opposite connections is odd, you have a balancing loop. If the number of opposite connections is even (or zero), you have a reinforcing loop.

You can think of a reinforcing loop as a dynamic that is amplified with each turn around the loop. Something like interest in a bank account is a virtuous reinforcing loop in that with each turn, you're compounding interest and making more and more money. Something like the tragedy of the commons is a vicious reinforcing loop, where each person takes more and more and eventually wipes out the shared resource. In many contexts you can think of virtuous cycles as making the situation better and better over time while vicious cycles make things worse over time.

Balancing loops have a muting effect with each turn. A thermostat is what we call a stabilizing balancing loop in that with each turn, the thermostat works to stabilize the temperature to a set goal. In social systems, stabilizing loops can be thought of as forces that keep things from getting worse (e.g thwarting violent escalation). A government crackdown on a group behind a pro-peace movement can be a stagnating balancing loop in that it keeps things from getting better or changing for the good - as progress is made, certain acts set back progress and even undo whatever gains were made. Stagnating loops can be thought of as ones that keep the situation from getting better (e.g. thwarting reform).

Combine those loops into an overall map that captures the "deep structure"

This is often as much art as discipline and usually isn't done as a large group process. Often this falls to a small team working on behalf of the larger group to create an initial draft that takes the many loops and sub maps that groups have created and digests them into a cohesive map that captures the "deep structure" of the system.

Be careful not to drive yourself (and others) crazy by trying to include every last detail. We can think of maps as of primarily two types, those representing detail complexity (every possible connection and factor) and those representing dynamic complexity (only the core dynamics at play in the system). In this case, we're trying to create a map that presents a comprehensive picture of the overall dynamics, while still being comprehensible. In a dynamic map you privilege showing only the factors and connections that form dynamic feedback loops as opposed to showing all the connections between factors. The standard to apply when deciding to add detail is to ask whether including the factor or loop does more to further understanding of the overall system then it does to confuse things. If it fails this test, then leave it out.

Socialize the map for feedback, revise and repeat

Especially when you're creating the overall map on your own or in a small team (out of the larger group setting), it's important to socialize the map and help people understand where their contributions (whether wording of factors, certain loops, or other ideas) fit into the end result. Be open to asking whether the map has any gaps or distortions and if it accurately captures their new understanding of the system.

If you're simplifying, combining, and changing language, it can be hard for people to see themselves in the map. I can’t stress it enough - the group has to own the final map. If they don't, teams won't use the map when prioritizing strategies and making sense of both the successes and struggles they face.

Great, you have a map. Now what?

At this point, hopefully you've been able to start aligning peoples' mental models about both what the system is and what needs to change in the system, and have some agreement about strategies and priorities. It's important that you don't put the map down at this point and never return to it.

But, how do you keep people coming back to the map?

Stay tuned for Part 2 of our conversation with Rob, when we discuss evaluating strategies using a systems lens and along with how to build an on-going learning framework.

Looking to dive even deeper into Rob’s approach? Pick up a copy of his book Making Peace Last.